Along with Roc Capital, LendingHome was among the fastest growing home-flip lenders in 2017. It uses an online platform that allows home flippers to apply for a loan by answering a brief questionnaire, and the company can close on the loan in a matter of days; traditional lenders typically take much longer. (LendingHome also offers traditional mortgage services.)

The flip side of the platform is that it allows individual accredited investors, or individuals who either make $200,000 per year or have a net worth of more than $1 million, to invest in individual pieces of those loans. The company also manages funds comprised of fix-and-flip loans that larger institutions such as banks or hedge funds invest in. Investments in the funds can be as much as $40 million.

Dozens of other companies tried and failed to enter the space in recent years. Companies such as Anchor Loans, LendingOne, and even traditional banks or hard-money lenders have similar offerings. In what may be the clearest sign yet that traditional banks are ready to get into home flipping, Genesis Capital, an offline fix-and-flip lender, was acquired by Goldman Sachs in 2017.

Fix-and-flip loans have also been securitized into bonds, similar to the way Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae bundle mortgages into bonds called mortgage-backed securities, which are sold to investors. LendingHome issued $53 million in fix-and-flip-backed securities in 2016. Angel Oak Capital, which is affiliated with a number of separate Angel Oak real estate lenders, including a fix-and-flip lender called Angel Oak Prime Bridge, issued $90 million in securities in March backed by fix-and-flip loans issued by its Prime Bridge affiliate.

If these online platforms using data to connect home flippers with investors sound familiar, it’s because new companies formed in the wake of the housing bust have applied similar FinTech concepts to virtually every stage of real estate transactions.

Opendoor and OfferPad, dubbed “iBuyers,” use online platforms and data analysis to buy houses from people looking to move, and the automation and algorithmic pricing allow the companies to close on deals in days. A similar company, Knock, uses an online platform to buy customers’ next homes and, after they move in, sells their previous homes.

The effects of institutional capital turning home flipping into a financial product is open for debate. Affordable housing advocates say home flipping puts upward pressure on rents and home prices, thus contributing to affordability concerns that have arisen as housing markets across the country recover from the housing bust a decade ago.

Research from these economists goes so far as suggesting that the home flipping frenzy was responsible for that crash. It showed that the rise in mortgage debt was driven by investors and speculators with good credit, and when defaults started to rise, those investors and speculators simply let their investment property go into default, leading to the collapse.

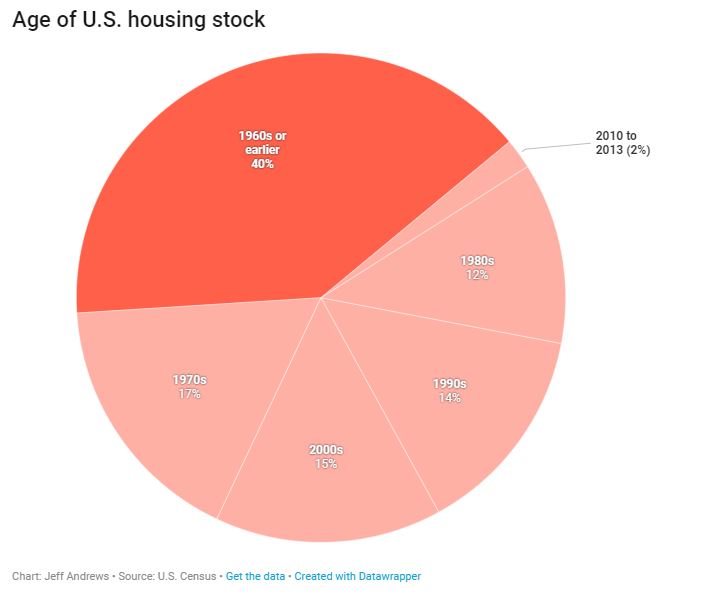

“Millennials simply aren’t going to buy something old and rundown and fix it up,” said LendingHome CEO Matt Humphrey. “This network is what keeps the housing market fresh. We are financing loans with a fair price, and to borrowers that will exit their homes often to first-time homebuyers who, in turn, won’t have to pay as high a price for their home because the lending was fair. This cycle makes communities stay revitalized. If the loans are done right, this is net-net good for communities nationwide. That’s the fundamental difference to how we do it, compared to the country club style.”

Originally Published www.curbed.com